Halo and the Power of a Killer App

What one of gaming's most successful launches can teach brands and startups in an AI-first world.

Thanksgiving week, 2001. I was a year into my management consulting job in Boston and looked forward to taking a break from the grueling hours. But with my parents living abroad and my roommates and friends planning to be with their families, I decided to spend the holiday in New York City with my best friend from college.

The draw? He had recently moved into his own place and had just picked up an Xbox, Microsoft’s first-ever gaming console, which launched the week before. He also couldn’t stop gushing over a new first-person shooter (FPS) game called “Halo: Combat Evolved”, an Xbox exclusive.

As a longtime PC gamer and FPS player—nerd alert 🤓—I had my reservations about how the genre would translate to consoles. Nonetheless, I drove down a snow-plowed I-90 on that Wednesday and picked up two six-packs of Coors Light on my way up to his apartment.

What happened next will be forever etched in my memory: three days and quasi-all-nighters in which we beat the game’s campaign in split-screen co-op mode, the two of us glued to the visceral experience of defeating an unstoppable horde of aliens, in a race against time to unlock a mysterious galactic artifact.

It felt like we starred in our own Hollywood blockbuster. The whole thing was presented in category-defining high-definition graphics, immersive 5.1 surround sound, and intuitive controller mechanics that put us in the shoes of a space marine — scratch that, the Spartan supersoldier: Master Chief.

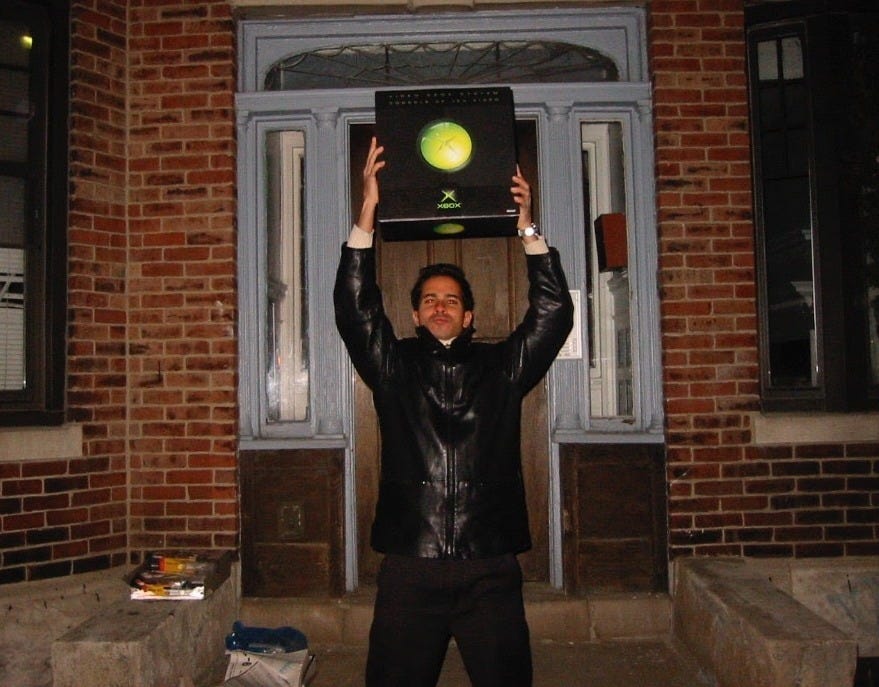

I was sold. When I got back home, I went straight to the Virgin Megastore on the corner of Newbury Street and Mass Ave and plunked down my cold, hard cash to buy my own Xbox and copy of Halo. I’ve owned every generation of the console ever since.

The power of a killer app

By launching Xbox with Halo, Microsoft delivered something unique for its time: a cinematic gaming experience, perfectly showcased by a title that took full advantage of the console’s power out of the box.

Halo became one of the most successful launch titles in console history, boasting a 50% attach rate on every Xbox and 6 million units sold over its lifetime. It also helped Microsoft officially enter, expand, and redefine the gaming market over several years, despite many believing it would fail.

Today, it’s a launch moment that stands the test of time because it encapsulates what every new product, platform, or service requires for a successful marketing debut: a killer app—the one experience so good that it makes buying into an entire platform worthwhile.

In a competitive market, Halo proved that the Xbox wasn’t just viable out of the gate but also ushered in something differentiated and possibly better for the console industry.

That’s what makes it an all-time killer app. That’s what makes it remarketable.

At a time when AI-led innovations are taking the world by storm and market expectations are at an all-time high, the need for vendors, large and small, to differentiate themselves through similar and tangible use cases has never been more critical.

So let’s rewind the clock and revisit what made Halo a shining example of the above, and how we can apply the lessons from Microsoft’s playbook today

The state of play in 2001

In the fall of 2001, you’d be excused if you thought Sony had already run away with the gaming console market. The PlayStation 2, launched a year earlier, had sold over 20 million units and offered hundreds of games.

Nintendo launched the GameCube, its next-generation console, three days after the Xbox, but it had decades of brand loyalty and a beloved catalog of characters and franchises at the ready.

Microsoft? A noob by comparison. Yes, the software giant had published a few PC games over the years (e.g., Flight Simulator and Age of Empires), but had little to no console experience.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, however. Microsoft’s original mission -- “a computer on every desk and in every home” was essentially complete. But as the home theater equipment market took off, fueled by the explosive demand for DVDs, which had grown 284% over the past two years, it was clear that the living room was the next frontier.

Sony knew this. Each PlayStation 2 came with a built-in DVD player, a format the Japanese multinational had heavily championed. The race was on: whoever dominated the living room would dominate digital entertainment for the next generation.

The Xbox team, led by Ed Fries, needed to make a statement.

“I need a weapon” - Master Chief

Hardware wasn’t going to be the issue. The original Xbox was essentially a bargain-priced gaming PC in a box. Microsoft knew how to build those and had extensive experience with controllers and peripherals from its PC gaming foothold.

Software also seemed straightforward. Unlike PlayStation’s custom platform, Xbox’s development software leveraged DirectX, a familiar standard for PC developers (ever wonder where the X in “XBox” came from 😉?). Having publishers port their games to the Xbox should be easy enough, in theory.

But ‘should be’ and ‘is’ are different things. Why would publishers invest in an unproven console platform?

Microsoft needed to demonstrate its vision would work. It needed proof that it could earn a space on every TV stand in every home. It needed a killer app.

Halo did the three things killer apps do remarkably well: it set a new standard, delivered a breakthrough user experience, and offered a glimpse of the future.

Enter Bungie Software.

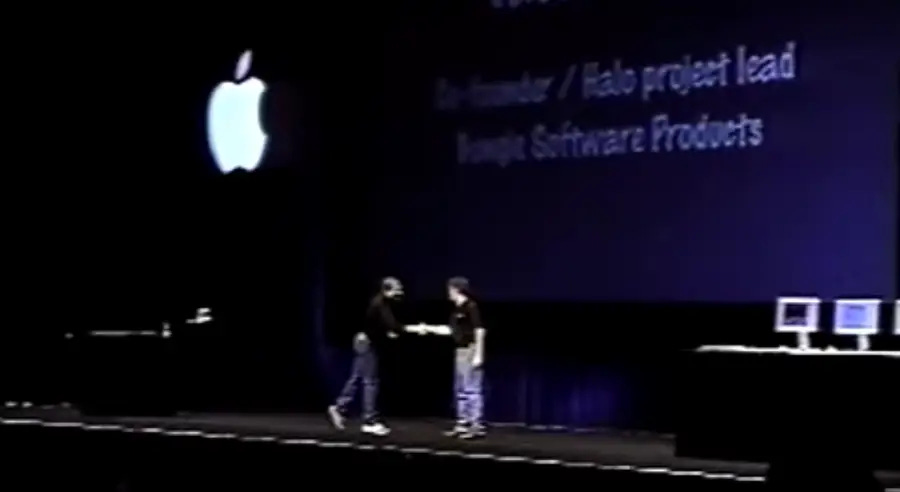

Bungie was a ten-year-old independent game studio founded by two University of Chicago students, Jason Jones and Alex Seropian. It found a niche following in the early 90s through technically impressive games made primarily for the Macintosh, such as the Myth and Marathon series (the latter influencing many of the gameplay mechanics and design philosophy seen in Halo).

By 1999, however, the studio was in financial trouble after a recall of Myth II and was looking for a buyer before it ran out of money. Halo was in development and had actually been previewed on stage at Macworld that summer by Steve Jobs himself.

The clock was also ticking for the Xbox team. They needed a solid library of games by Christmas 2001. When a Bungie executive approached Fries about a potential sale after the Macworld announcement, it wasn’t just serendipitous; it was the Hail Mary the Xbox team needed.

Bungie agreed to be acquired by Microsoft for $30M, with Halo slated to become a first-party console exclusive. The rest, as they say, is gaming history.

Game of the Year

Halo garnered massive praise at launch. In addition to its groundbreaking graphics and cinematic presentation, it was hailed for successfully bringing the FPS genre to consoles in a big way. The game’s positive word of mouth, multiple Game of the Year awards, and long-tail sales through 2002 made it not just a system seller for Xbox, but the system seller. It was the reason consumers bought the Xbox.

Halo did the three things killer apps do remarkably well: it set a new standard, delivered a breakthrough user experience, and offered a glimpse of the future.

Setting a new standard

Until Halo, most FPS games were played on PCs because of the standard mouse-and-keyboard controller scheme, which gave players confidence in their ability to move and aim with precision. While console FPSes did exist, some with even a cult following like GoldenEye 007, they were plagued by awkward controls.

Bungie addressed this by making full use of the Xbox controller’s mapping and ergonomics at launch: left thumbstick for movement, right thumbstick for aiming, triggers for firing, and face buttons for actions like jumping, reloading, and switching weapons. Sounds simple, right? But here’s where they really broke the mold.

Bungie designer Jaime Griesemer engineered what they called “sticky aim”, an invisible layer of input interpretation that made thumbstick aiming and movement feel as precise as a mouse and keyboard.

They also ensured that Halo’s action felt seamless through a new integrated combat system. For the first time in an FPS, players could lob grenades while keeping their weapon up, or melee enemies without holstering, or jump out of moving vehicles.

Put together, Halo combined precise player movement and combat actions into a fluid moveset and layout that became the standard for every major console shooter ever since.

Delivering a breakthrough user experience

It’s not an exaggeration to say that playing Halo felt like being dropped into one’s very own Hollywood blockbuster.

The final release of the game dripped with production values.

From the iconic Gregorian chant that guided you through the load menu and punctuated other epic moments in the game, which game composer Marty O’Donnell wrote it in three days, to the magnificently rendered 3-D environments that made it feel like you were interacting with a massive open world for which the game won many DICE awards (think gaming’s Oscars), to the tactile feedback you’d get via the controller each time you’d fire a weapon or sustain damage--all of these elements made for an elevated and differentiated user experience, powered by the Xbox.

Years later, Hideo Kojima, the revered game auteur and producer who worked on flagship titles for Sony such as the Metal Gear Solid series, would credit Halo as one of the releases that sparked a significant shift in what big-budget games could look and feel like in the early aughts.

Offering a glimpse of the future

Last but not least, Halo offered a compelling glimpse at what the future of online gaming could look like from the comfort of one’s couch.

It started with Microsoft’s bet to be the only manufacturer to ship its console with a built-in 10/1000 Ethernet port, enabling console-to-console play via local area networks (LAN) and future-proofing it for online gameplay via broadband.

It was a gutsy move because high-speed internet had yet to take off in most households, but it was also prescient.

Halo supported competitive multiplayer gameplay for up to 16 players by connecting up to 4 Xbox consoles over a local network. PC-savvy and college-aged players saw it as a cheap, relatively hassle-free way to quickly organize LAN parties — a PC-gamer staple —that rapidly became a pillar of Halo’s early growth and cultural popularity.

This is where Microsoft bringing its PC ethos to the console wars paid off. Halo became a party and dorm favorite through addictive and robust multiplayer modes because of the Xbox’s powerful networking capabilities. It also socialized Microsoft’s vision for the future of console gaming: not just split-screen and social, but online — brilliantly setting the stage for what would become their Xbox Live service a few years later.

What’s remarketable about Halo today

Twenty-four years later, Microsoft’s Halo playbook offers many repeatable tactics for brands seeking to differentiate themselves with a killer app, as well as valuable lessons on which pitfalls to avoid.

Most remarketable- Disrupting the status quo: Halo’s controller scheme is now gospel for every console shooter, from Call of Duty to Fortnite. In business, it’s not often that you get to reinvent the way things are done. But Halo did it for the FPS genre, the same way Uber did it for public transportation, and Apple did it for smartphones. Consoles represent the largest share of the FPS market today because Halo made the genre more viable and approachable--your reminder that killer apps often disrupt the status quo by showing consumers “a better way”.

Most remarketable - Master Chief = Xbox: Fries and his team may not have planned on it, but Halo’s powerful sci-fi protagonist rapidly became synonymous with the Xbox brand, helping position the console as the more technically powerful gaming platform. That imprimatur helped them attract a coterie of technically ambitious developers and titles over the following years, including Ubisoft’s Splinter Cell, which was first developed for the Xbox as a technical showcase and later downported to PS2 and GameCube. By leaning into this halo effect, pun intended, Xbox became a tractor beam for development, a massive win for any aspiring platform.

Least remarketable - “The Duke” and alienating Japan: While Halo’s controls were revolutionary, the Xbox’s original controller, nicknamed “The Duke,” was much less so. Comically oversized, it was of a piece with the console’s overall clunky aesthetic. The feedback from Japanese developers, in particular, was immediate and harsh, with many third-party publishers postponing development conversations until ergonomic concerns were addressed. Microsoft had to rush out the slimmer “Controller S” within months, pushing the Japanese launch to 2002, by which time the damage to perception had already been done. This, coupled with other cultural missteps, such as over-reliance on Western-centric games at launch and perceived arrogance and tone deafness during negotiations with local publishers, compounded its woes. Xbox sales bombed in Japan, with fewer than 10% of first-generation consoles sold there during its lifetime.

Xbox’s Japan woes may not have been preventable, but they serve as a reminder that a killer app is not a silver bullet.

More often than not, different markets will require different approaches. In the enterprise software space, for example, it’s great to have a big Fortune 500 logo to lead with in your marketing assets, but that logo is meaningless if it doesn’t resonate with your intended audiences at a local, cultural, or aspirational level.

Specs don’t create loyalty—memorable experiences do.

Why AI needs its Halo

The parallels between the console wars from 2001 and today’s AI wars are hard to ignore.

AI companies are burning through billions in cash on compute infrastructure and racing to deliver more capabilities at lower prices. OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and others are locked in what feels like a specs war — over which models score higher on benchmarks, which can process the most tokens, and which can integrate with the most workflows — all while chasing users at a net loss. The same users who, by the way, go back and forth between models because they all do similar things.

Sound familiar? It’s the same loss-leader strategy console manufacturers have run over time. But the difference is that each has a killer app users swear by, keeping them loyal. Microsoft has Halo, Nintendo has Mario, and PlayStation has Miles Morales.

ChatGPT had a running start when it proved in late 2022 that LLMs could actually work and were here to stay. But within months, everyone had a chatbot.

Today’s AI competition feels less like a race to create breakthrough experiences and more like a race to raise and blitz-scale while investor sentiment is strong.

It’s a pity, because within that envelope lies a genuine opportunity for companies to innovate further by delivering transformative moments people are willing to pay for: AI-powered experiences that feel magical because they redefine how things are done.

Vertical AI companies seem to be the closest to delivering a killer app right now, whether it’s legal research and workflows that change how attorneys work (Harvey), agentic AI-powered customer service experiences that boost bottom lines (Sierra), or low-code platforms that deliver an army of engineers and designers with every prompt (Lovable).

The cost of not having a killer app

Want to see what happens when you skip the killer app? Look at Apple’s Vision Pro.

Despite jaw-dropping specs and Apple’s undeniable innovations, Vision Pro launched to the public without a buzz-worthy use case that triggered a “holy shit you have to try this” moment. At $3,500, it promised immersive experiences for work and play, but nothing you couldn’t experience for far cheaper through other means or that didn’t require you to wean yourself away from the world.

As a gadget geek who’s all in on the Apple ecosystem across music, movies, and TV, I tried it but couldn’t justify pulling the trigger.

The Vision Pro is a textbook example of what happens when you lead with specifications instead of use cases. Even Apple—with its infinite resources and history of entering established categories late and still winning—couldn’t make its new platform succeed without delivering that one experience that makes people truly care.

Finish the Fight

Here’s what Microsoft taught us with Halo: products and platforms don’t sell on specs—they sell on proof.

Halo was an experience so compelling that it justified buying into a new console platform. The system, with its bulky and then not so bulky controllers, the built-in broadband service, were all worth it because of those split-screen and online sessions that ran until 3 AM.

Twenty-four years later, that lesson is more relevant than ever.

If you’re launching something new—whether it’s in AI, AR, or whatever comes next—ask yourself: what’s your killer app?

Not your specs. Not your benchmarks. But that moment of proof, that time to value, that makes someone realize things have changed for the better, and they can’t wait to do more with your solution.

That’s what I remember about my first time playing Halo. Not the Xbox’s GPU or RAM specs or other technical wizardry. It was knocking back silver bullets with one of my best friends, playing well into the night.

Specs don’t create loyalty—memorable experiences do. In a crowded marketplace, launching with a killer app may not guarantee you victory, but much like having the Master Chief by your side, it gives you a fighting chance.